The Urgency and Complexity of Moving Beyond GDP

Efforts to explore how the portfolio of capitals that make up Comprehensive Wealth—financial capital, produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and social capital—can give policymakers insights into how their policies build wealth for their countries in the long run.

How can decision makers build sustainable policies when they only see part of the picture of their countries’ economic performance? How can citizens gauge if their children or grandchildren will enjoy better lives when the primary goal of much national policy—GDP growth—aims only at maximizing short-term income? What alternative measures could complement GDP and give a fuller sense of a country’s prospects for wellbeing?

These questions will be in the spotlight during the Summit of the Future at UN Headquarters in New York on 22 and 23 September. UN Secretary-General António Guterres has described the two-day event as an “opportunity to enhance cooperation on critical challenges and address gaps in global governance.”

The draft outcome document world leaders will endorse at this Summit—the Pact for the Future—features a number of commitments to transform global governance, including “Action 56. We will develop a framework on measures of progress on sustainable development to complement and go beyond gross domestic product.” It’s a pledge that aligns with a growing chorus of voices underlining that the 20th century trend of prioritizing income measures like GDP in policymaking creates a distorted, short-term view of progress.

Just which indicators will be included in that “framework of measures of progress” is uncertain, though thought leaders and organizations have been developing robust options for years. For roughly a decade, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) has been exploring how the portfolio of capitals that make up Comprehensive Wealth—financial capital, produced capital, natural capital, human capital, and social capital—can give policymakers insights into how their policies build wealth for their countries in the long run. A recent panel discussion on Moving Beyond GDP Through Comprehensive Wealth explored the advantages and challenges of leveraging national data in Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Trinidad and Tobago to track how changes in those countries’ comprehensive wealth over a 25-year period tell different stories than GDP performance. Robert Smith shared the report’s findings on behalf of his IISD colleagues Livia Bizikova and Zakaria Zoundi as well as the in-country teams. After exploring the nuanced benefits and failings of GDP as a measure of national progress, he presented the five elements of comprehensive wealth as an answer to UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ call to “shift priorities towards new metrics.” The five elements of comprehensive wealth are:

- Produced capital, which consists of roads, railways, ports, houses, machinery, and the wide variety of other manufactured assets found in the economy;

- Natural capital, which includes market natural resources such as timber, minerals, oil, and gas. It also includes ecosystems of all kinds; for example, wetlands that help create clean drinking water and forests that act as carbon storehouses;

- Human capital, which is made up by the collective knowledge, skills, and capabilities of the labour force—the result of lifelong learning in both formal and informal settings;

- Financial capital, which covers stocks, bonds, and other forms of financial assets. Investments by governments, businesses, and households are often aimed at building up stocks of produced and financial capital; and

- Social capital, which represents the norms and behaviours that define interactions between members of society, including how safe people feel in their communities, inclusivity, and trust in important institutions.

Noting that most of the data for the reports were drawn from national sources, Smith presented each of the three country’s comprehensive wealth indices for 1995 through 2020 compared to their GDP performance.

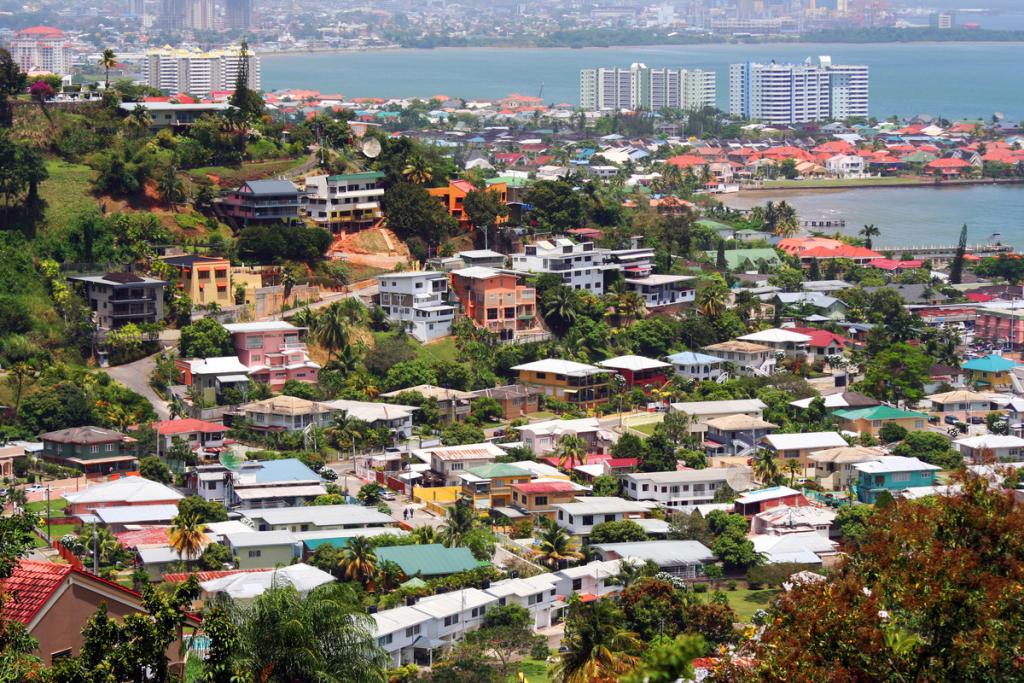

While the GDP index in Trinidad and Tobago went up “reasonably nicely” over the study period, Smith noted the comprehensive wealth index hardly changed from 1995 to 2020. He said that when a country grows its GDP but not the asset base on which that GDP rests, it likely indicates a sustainability problem. He drew attention to the measure of Trinidad and Tobago’s natural capital reaching a zero value in 2020—a reflection of the loss of value in oil and gas that has powered the island nation’s economy. Given that half of the country’s produced capital is tied to the oil and gas sector as well as the human capital invested in skills for the same industry, the decline in natural capital paints a different—and more dire—picture of Trinidad and Tobago’s economic sustainability than GDP performance. Smith noted that if comprehensive wealth was regularly studied and reported in the country, it would prompt dialogue among policymakers and citizens on how to create an economy that would ensure long-term wellbeing.

In Indonesia, Smith noted that while there was good growth in the comprehensive wealth index at 4.3%, GDP grew only 2.8% during this period. In other words, the amount of income (GDP) created for each unit of wealth in Indonesia went down over the study period. Smith said this is highly undesirable and unusual, as countries typically get better at converting wealth into income over time. He noted that if Indonesia had maintained its level of productivity from the start of the study period (1995) to the end (2020), the country would have 42% more income now than it currently does—a sum that would have pushed Indonesia closer to becoming a high-income country. While this decline in productivity revealed by comprehensive wealth should obviously interest Indonesians, Smith pointed out that Indonesia’s management of its wealth—especially its world-class natural capital—has global implications. The country is a steward to a great amount of biodiversity, including the largest expanse of rainforest in all Asia.

For Ethiopia, Smith said the study revealed good progress on increasing overall wealth despite social, environmental, and economic challenges. However, with overall comprehensive wealth in the country starting from a low point at the beginning of the study period—just one-tenth of what it is in Indonesia or Trinidad—Ethiopia has further to go in raising its CWI to sustainably improve wellbeing. Smith suggested that produced capital investments made to develop the manufacturing sector could be better invested in modernizing the agricultural sector, which currently drives much of the country’s GDP performance and is labor intensive with low productivity.

After noting trends in specific capitals of comprehensive wealth across the three countries, Smith emphasized the need to expand engagement from the researchers involved in the study with more national statistical office staff, central banks, and policymakers. With comprehensive wealth revealing insights that are obscured by a focus on GDP performance alone, he said governments have an opportunity to use evidence to shift away from “short term-ism” to evidence-based planning for sustainable well-being. He concluded by sharing quotes from youth who had recently submitted essays on the need to move beyond GDP.

During a panel discussion, André Loranger, Chief Statistician of Canada, Statistics Canada, agreed many elements of material progress aren’t captured by GDP. He noted that Canada’s GDP in 2023 stood at about $3 trillion, or roughly $73,000 per person, with annual growth at 1.2%—and that these numbers revealed little about society in general and wellbeing. He pointed out that Statistics Canada was the first national statistics office to include natural resources in its quarterly balance sheet accounts. Statistics Canada has also been working to measure human capital in line with work being advanced in the United Kingdom. He suggested the Summit of the Future would be a forum to advance alternative measures to GDP to help meet share global challenges, while also pointing to the work of the UN Network of Economic Statisticians and the UN Committee of Experts on Environmental-Economic Accounting in advancing interoperable frameworks tackling economic, the environmental, and social statistics. He also noted the recent draft of the Pact for the Future outcome document of the Summit of the Future suggests establishing an independent high-level expert group to develop recommendations for going beyond GDP, which provides another sign of the growing international momentum to revise the statistics that guide policymaking decisions.

Grzegorz Peszko, Lead Economist in the Global Platforms team of the Environment, Natural Resources & Blue Economy Practice Group, World Bank, noted his organization has been measuring wealth for more than 20 years, with the late Kirk Hamilton coining the term comprehensive wealth. He said he finds comprehensive wealth a good complement to GDP, as it is future oriented and could help ensure upcoming generations have at a chance to enjoy the same production and income levels as the current generation. He agreed comprehensive wealth reports would have helped decision makers in Trinidad and Tobago get earlier “yellow flags, then red flags” on its economic path. He added that the World Bank is interested in looking at countries’ experience in compiling comprehensive wealth sums for a wide range of asset classes, and gauging whether countries can replicate this bottom-up statistical work to improve on previous top-down estimates.

Tom Bui, Director of Environment, Global Affairs Canada, said he approached the day’s discussions with a background of investing, given his previous experience at the International Finance Corporation, the Green Climate Fund Board, and the Global Environment Facility. He related how, when reviewing a multibillion-dollar investment in the Nam Theun 2 hydroelectric dam in Laos, the indicator that won his vote was a measure of income—the addition to public revenue that would come from exporting electricity—rather than the impacts on natural capital. He added that his investment decisions have generally lacked indicators on the potential to add value to natural, human, or social capital. He asked other panelists, “When can we have a system of national accounts that capture all of this stuff?”

Chris Barrington-Leigh, Associate Professor, Department of Equity, Ethics and Policy & the Bieler School of Environment, McGill University, questioned the motivation and aims of developing complementary measures to GDP. He noted that a comprehensive wealth index could be buoyed by large growth in productivity, masking declines in ecosystem health or migration instability.

Commenting after the event, Pushpam Kumar, Senior Economic Advisor and Chief Environmental Economist, UN Environment Programme (UNEP), said moving beyond GDP through measuring all types of wealth—produced, human, and natural—would help us keep track of our progress and the sustainability of the economy. Identification, assessment, accounting, and valuation of natural capital would also provide humanity a compelling basis for investment into combatting climate change, halting biodiversity loss, restoring degraded land, and reducing pollution.

The complexity of this discussion—and the need for national policymakers to better emphasize the long-term impacts of their decisions—underlines the difficulty of the task set out for the “independent high-level expert group” the Pact for the Future calls for to examine next steps. Whether the beyond GDP conversation rises to prominence during the Summit of the Future is also uncertain, with so many action items and current crises competing for attention. What is certain, however, is that without reliable data on whether countries’ policies are sustainable in the long-term, it will be difficult to build the healthy and just world future generations deserve.

You might also be interested in

Moving Beyond GDP Through Comprehensive Wealth

An analysis of wealth in three countries shows how GDP gives policy-makers and people a misleading story of progress—and why we must shift indicators.

Comprehensive Wealth in Ethiopia

Ethiopia has made progress in expanding its comprehensive wealth despite social, economic, and environmental challenges—but there is room for growth.

Comprehensive Wealth in Trinidad and Tobago

The compilation of comprehensive wealth measures for Trinidad and Tobago from 1995 to 2020 reveals unsettling trends that GDP keeps invisible.

Comprehensive Wealth in Indonesia

A comprehensive wealth report for Indonesia reveals aspects of the country's development that are invisible through the lens of GDP growth alone.