Turning Down the Temperature: Freezing HFCs as a critical step in climate action

This past week, climate negotiators gathered in Rwanda's capital Kigali to once again test the international community’s political resolve to tackle climate change, this time on a class of short-lived greenhouse gases called hydrofluorocarbons.

On October 14, a historic agreement was reached to freeze and then eliminate, over the next few decades, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), a potent class of greenhouse gases used in air conditioners, aerosols and insulation foams.

This is the second historic deal on global climate action reached this month. On October 6, the international community agreed on a global, market-based approach to address emissions from the international aviation sector starting in 2021. These mitigation measures show the continued momentum of realizing commitments made under the Paris Agreement. They also demonstrate the importance of specific, focused time-bound agreements to tackle climate change.

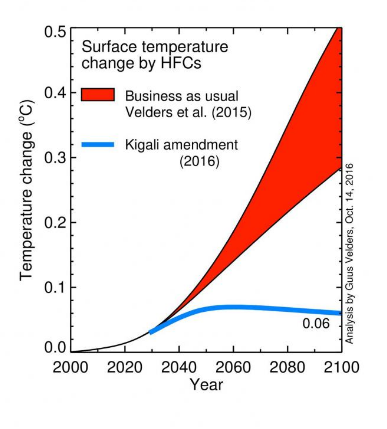

The agreement reached this past week in Kigali is the single biggest climate commitment ever, averting almost 0.5 degrees Celsius of global warming. It commits developed countries—such as the United States, Canada, and members of the European Union—to begin a phase down of HFCs by 2019. Developing countries—including China, Brazil, India and many African countries—have agreed to freeze HFC consumption by either 2024 or 2028.

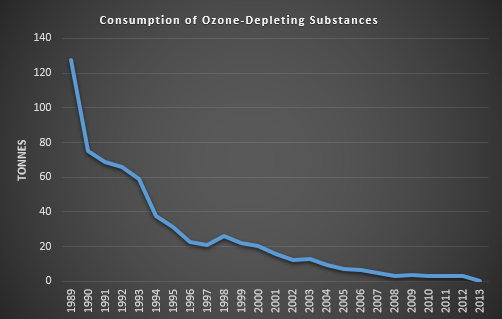

The Kigali agreement embeds the successful model of the Montreal Protocol. In the past 30 years, the Montreal Protocol has played a critical role in helping the ozone hole recover, with a recent study noting the emergence of a healing in the Antarctic ozone layer. By 2005, the Montreal Protocol was successful in reducing ozone-depleting substances by over 95 per cent or near 1.7 million tonnes, and avoided emissions of several billions tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. It has generated over USD 3 billion of funding to help developing countries meet their commitments under the agreement. In the United States alone, the success of the Montreal Protocol is estimated to result in 6.3 million skin cancer deaths avoided by the end of the century, with health care savings of over USD 4 trillion from 1990 to 2065.

For 30 years, the Montreal Protocol has brought together some key policy elements that were repeated in Kigali: strong scientific evidence of the atmospheric and climate effects of HFCs, collaboration with researchers and industry to identify and scale up substitutes, securing new and additional funding to assist developing countries in meeting reduction timetables, introducing a dual-track timetable for commitment implementation between developed and developing countries, and having a robust monitoring and compliance system to check ongoing progress.

HFCs are all around us—in air conditioners that cool our houses and cars, in aerosols and insulation foams. They are potent gases with global warming potentials hundreds of times greater than carbon dioxide (CO2). The most common type, HFC134a, used in automobile air conditioners, has a global warming potential that is 3,790 times that of CO2 (over a period of 20 years, with climate-carbon feedbacks).

Although HFCs represent a small fraction of climate pollutants in the atmosphere today, their production and use are rising at a rate of 7 per cent per year. Moreover, in some places they are the fastest-growing source of greenhouse gases. With a short atmospheric lifetime (HFC134a, for example, has a lifetime of 13.4 years), their increased use can pose a significant risk of short-term temperature increases. However, the good news is that HFCs are one of the lowest-hanging fruits in the global effort to combat climate change, with cost-effective solutions that are available today.

Despite the opportunities, the negotiations to phase out HFCs are no mean feat. Industrial activity, the growing global middle class, and rising temperatures will result in increased demand for low-cost cooling options. This requires solutions to address growing use of HFCs while avoiding undue burdens that would push people further into poverty and negatively impact quality of life and health.

Patching the ozone hole

In 1989, the international community agreed to reduce the production and use of products that were responsible for the depletion of the ozone layer. The resulting Montreal Protocol has been one of the most successful global environmental treaties. It has been incredibly effective in reducing ozone-depleting products, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Data source: European Environment Agency

The phase-out of CFCs was essential in reversing the damage done to the ozone layer. In addition, CFCs are potent climate pollutants, and their removal has had secondary climate benefits. For example, CFC11, which was used as a refrigerant gas, has a global warming potential 7,020 times that of CO2 (over a period of 20 years, with climate-carbon feedbacks). The phase-out of CFCs not only helped ozone recovery efforts but also resulted in about 10 gigatonnes CO2 equivalent of avoided emissions per year in 2010.

However, the growing global middle class combined with industrial growth have resulted in increased demand for production and use of substitute products such as HFCs. Much of the growth in HFC emissions is expected to come from developing countries.

Although significantly less damaging to the ozone layer, the climate impacts of HFCs were likely not top of mind when the Montreal Protocol was initially drafted. The more recent realization of the existential threat of climate change has put the spotlight on HFCs for a number of reasons, including their climate impact, the fact that there are cost-effective alternatives and because the benefits of action significantly outweigh the costs.

How low/fast must we go?

As with any climate pollutant with high global warming potential, such as HFCs and methane, the question shouldn’t be about the extent of reduction but rather how fast can we eliminate these sources of pollution altogether.

Left unaddressed, the rise of emissions from HFCs would have likely offset the success of the Montreal Protocol. Growth in HFCs would add near 9 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent of emissions by 2050 and result in temperature increases of up to 0.5 degrees by the end of the century. Preventing such a dramatic increase is especially important in a world where the goalpost has been set to keeping the rise in global average temperature to below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The United States, which has already begun regulating HFCs domestically, has championed a North American proposal and played a critical role in advocating for an ambitious, comprehensive approach for tackling HFCs. The agreement in Kigali has a number of key positive outcomes:

- It builds on the success of the Montreal Protocol, as an effective instrument and adds HFCs as a regulated gas under the protocol through an amendment.

- It sets milestones including one whereby developed countries will start to phase down HFCs by 2019, and developing countries will follow with a freeze of HFC consumption levels in 2024.

- Finally, financial support to offset the impact on developing countries will be discussed in Montreal in 2017. This funding will no doubt be complemented by recently announced USD 1 billion funding measure by the World Bank and another USD 80 million by donor countries and philanthropists.

North America—First movers can benefit from economic opportunities

The United States is already ahead, having introduced HFC regulations under the EPA’s Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) Program. A number of large US private sector companies have also thrown their weight in support of an accelerated phase-out of HFCs. As the world transitions away from HFCs, new products will create economic opportunities and will drive innovation. Those that get ahead of the regulatory curve will likely stand to benefit from tremendous opportunities presented by demand for substitute products.

For its part, Canadian regulators can work with their US and Mexican counterparts and continue on a path of strengthening a regional approach to climate policy. Better regulatory alignment will reduce compliance costs and can create economic activity on both sides of the border. Collaboration can also result in increased ambition while building on the North American leaders' commitment to working together to tackle HFCs.

Refer to IISD's Earth Negotiations Bulletin for detailed coverage of the Meeting of the Open-ended Working Group (OEWG 38) of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer and 28th Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol.

You might also be interested in

As U.S. and Canadian Climate Policies Diverge, How Do We Ensure Canada’s Competitiveness?

With relatively new administrations on both sides of the border, the United States and Canada have staked out opposing views on climate change. That has environmentalists and businesses worried. This has potentially damaging consequences for Canada’s trade competitiveness.

Unlocking Supply Chains for Localizing Electric Vehicle Battery Production in India

This study aims to highlight the key supply chain barriers in localizing electric vehicle (EV) battery cell manufacturing in India. It summarizes consultations with 12 companies, as well as experts and policy-makers, to determine the crucial challenges and opportunities in localizing battery manufacturing in India.

COP 29 Must Deliver on Last Year’s Historic Energy Transition Pact

At COP 29 in Baku, countries must build on what was achieved at COP 28 and clarify what tripling renewables and transitioning away from fossil fuels means in practice.

IISD Welcomes Draft Regulations for Oil and Gas Pollution Cap

A firm cap on emissions can provide certainty for industry to invest in decarbonization, while ensuring the sector is on a path to net-zero by 2050.