Re-Distributing Up: How fuel subsidy policy has short-changed Bihar

Despite significant social and economic progress in recent years, the development challenges facing the Indian state of Bihar remain profound. The state, one of the poorest and most populous in the Indian Union, goes to the polls for State Assembly elections in October 2015.

Among the issues currently under debate is the granting by the central government of “special category status” to Bihar, a classification that would give Bihar preferential treatment from the central government in terms of grants and disbursements to enhance the state’s development. This is a longstanding demand of state politicians across party lines, based on low levels of economic development as well as a sense of historical discrimination against the state within central government funding allocations.

A key issue often left out in these discussions on the fiscal relationship between the central government and poorer states is the inequality between states in the distribution of (centrally financed) fuel subsidies. In the past decade, fuel subsidies have collectively represented the single largest social transfer administered and funded by the central government. At the national level, the highly regressive social distribution of fuel subsidies—and in particular of diesel and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) subsidies—is well documented. Less widely understood is the structural discrimination between states inherent in both current and previous fuel subsidy policies, with consumers and businesses in India’s poorest states receiving a disproportionately low share of total subsidy transfers.

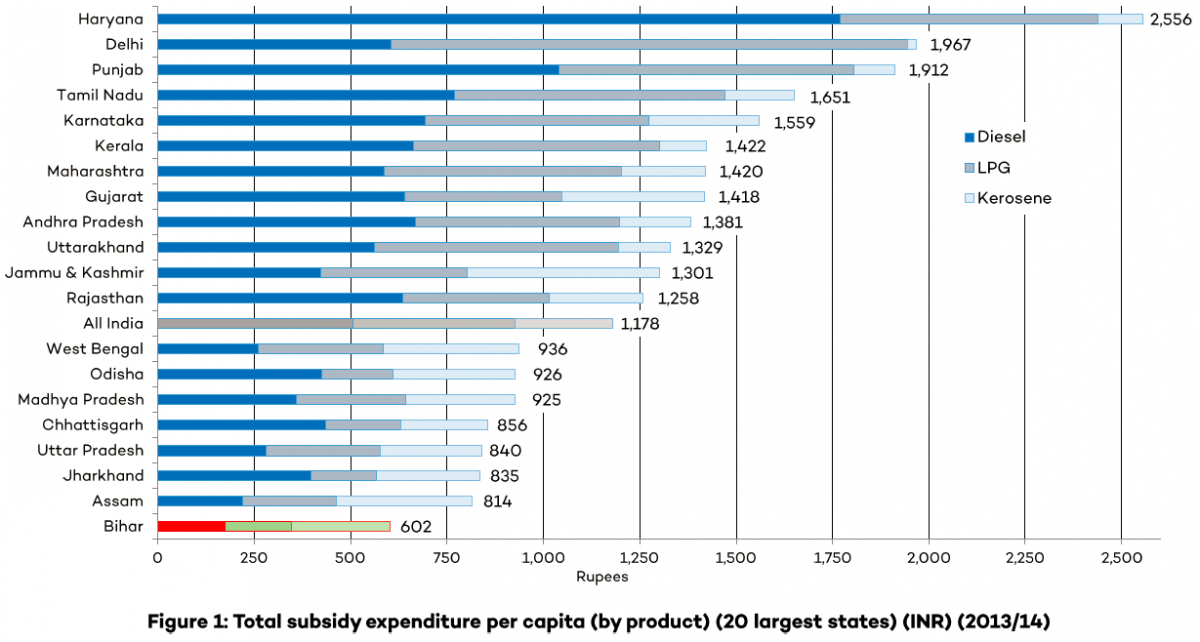

Throughout the previous decade, Bihar has consistently been the lowest per capita recipient of fuel subsidy transfers among all states and union territories. Figure 1 below shows total per capita subsidy expenditure for the 20 largest states and union territories in the 2013/14 fiscal year (FY) (the most recent year for which state-level consumption data is currently available), highlighting the scale of the disparity between states in the receipt of subsidy transfers. In FY 2013/14, Bihar received an average per capita transfer of INR 602 per person.[1] By comparison, Haryana received INR 2,556 per capita, Delhi received INR 1,967, Punjab received INR 1,912, and some smaller states and union territories received even more (for example, Goa received INR 2,903 per person).

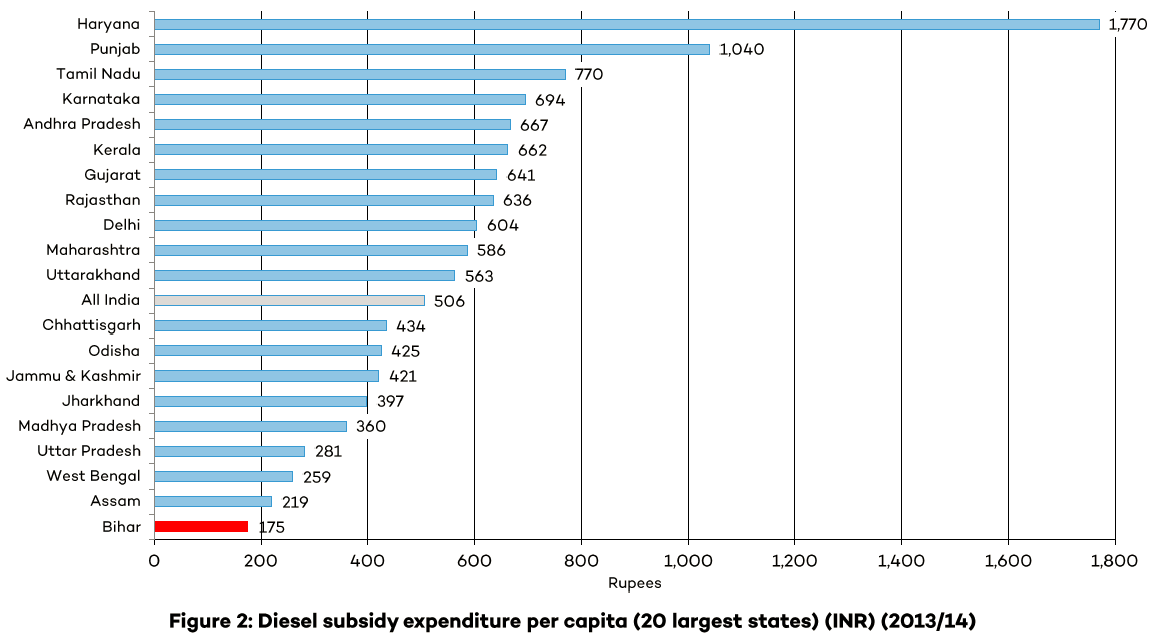

In FY 2013/14, Bihar was the lowest per capita recipient of subsidy transfers for diesel, receiving less than 10 per cent (INR 175 per capita) of the equivalent transfer received in Haryana (INR 1,770 per capita), the highest among major states (see Figure 2 below).

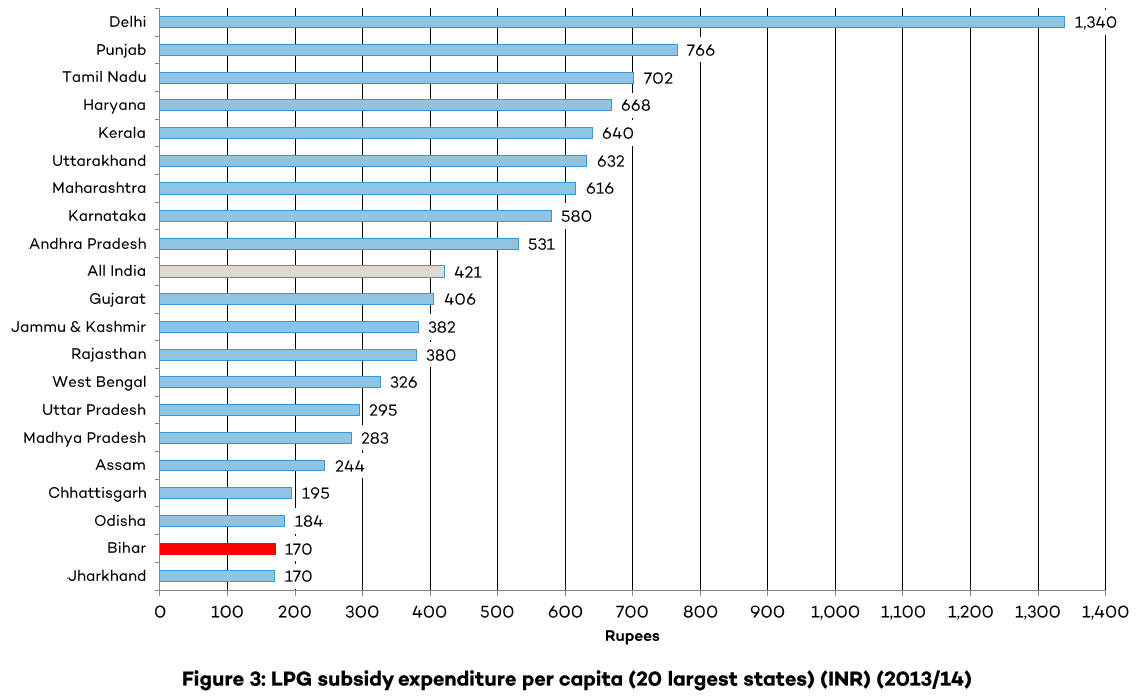

Bihar was also the second lowest recipient of subsidy transfers for LPG in FY 2013/14 (marginally exceeding only Jharkhand, and having previously been the lowest per capita recipient in FY 2012/13), receiving a per capita average of INR 170 (see Figure 3 below). This represented less than a sixth of the equivalent transfer in Delhi, which received INR 1,340 per person.

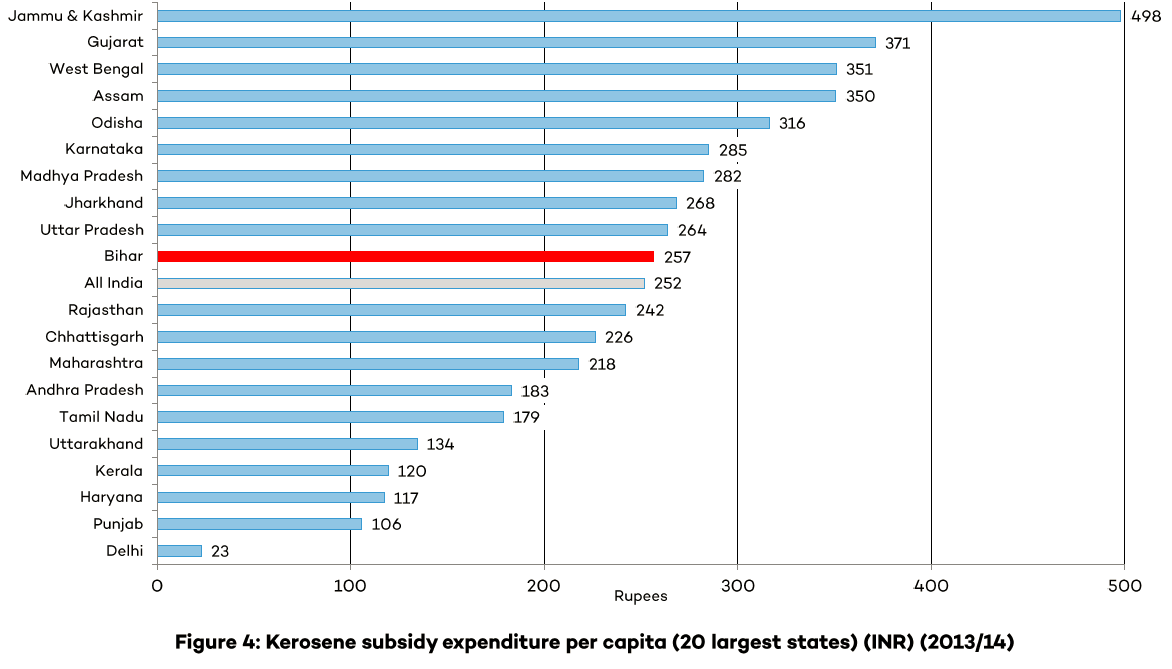

Despite being the poorest Indian state, and among the states with the lowest level of access to electricity and LPG, Bihar’s allocation of subsidized kerosene (the one subsidized product whose distribution is directly determined by the central government) was roughly equivalent to the all-India average at INR 257 per capita, with several wealthier states—most prominently Gujarat, at INR 371 per person—receiving far higher per capita subsidy allocations (see Figure 4 below).

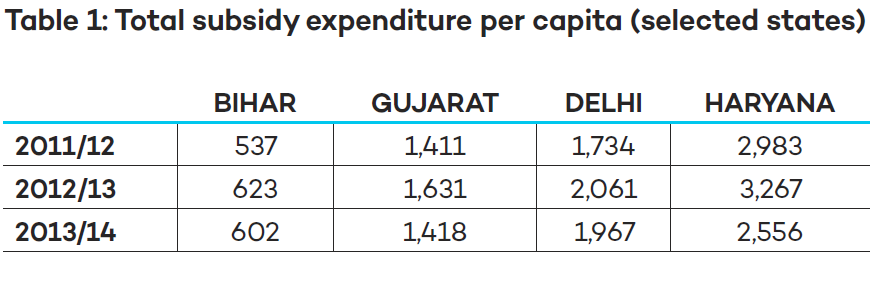

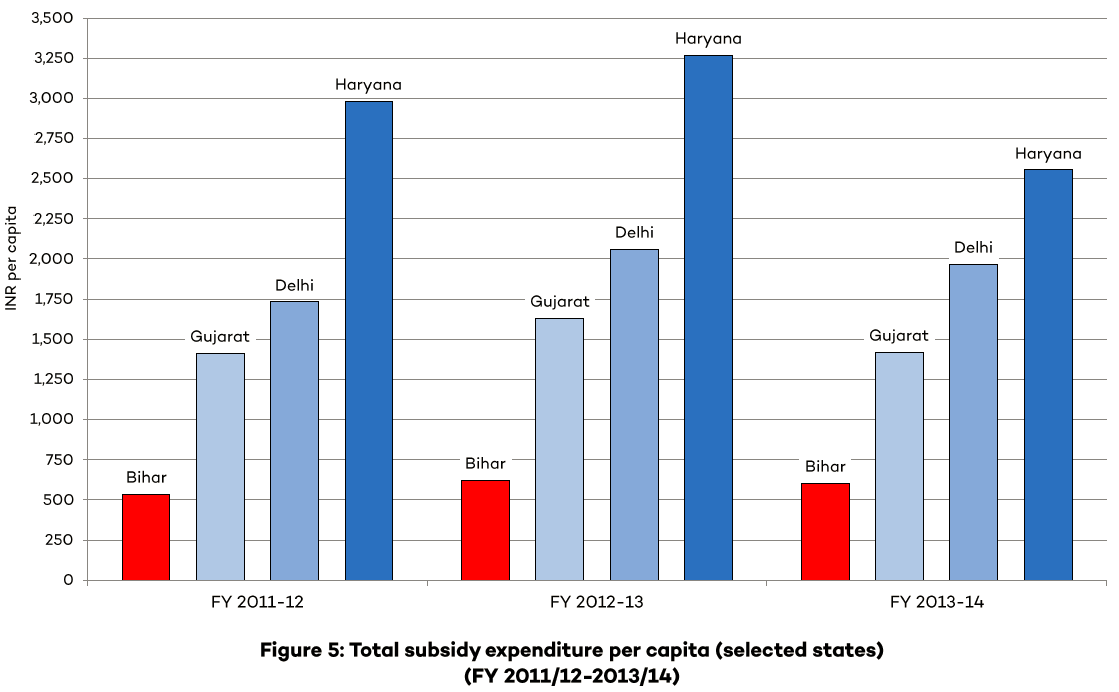

The cumulative effect of these distortions in subsidy expenditure (which are a direct result of central government decisions regarding the design and implementation of fuel subsidies) is massive, resulting in huge disparities in multi-year resource transfers. For example, in the three most recent years for which state-level consumption data is currently available (FY 2011/12 to FY 2013/14), the central government and associated public sector enterprises spent a total of INR 447,771 crore (USD 73.6 billion) subsidizing diesel, LPG and kerosene—over four times the equivalent central budget allocation to the flagship National Rural Employment Generation Scheme (NREGS) public employment program. During this period, Bihar consistently received the lowest per capita transfer of all states (at between INR 525 and 625 per person). Table 1 and Figure 5 below show the total per capita subsidy received in Bihar relative to selected states and union territories from FY 2011/12 to FY 2013/14.

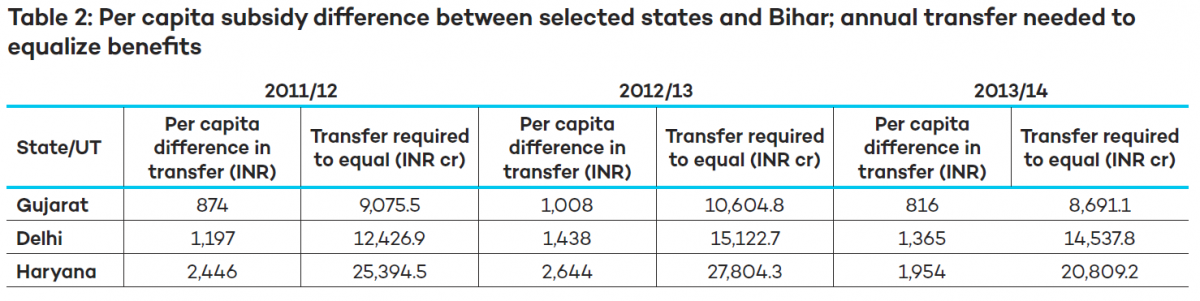

Table 2 shows the approximate per capita difference between the subsidy received in selected states and that received in Bihar for the three years to March 2014, and the total transfer required (on an annual basis) for Bihar to receive the same per capita transfer as that received in the selected states.

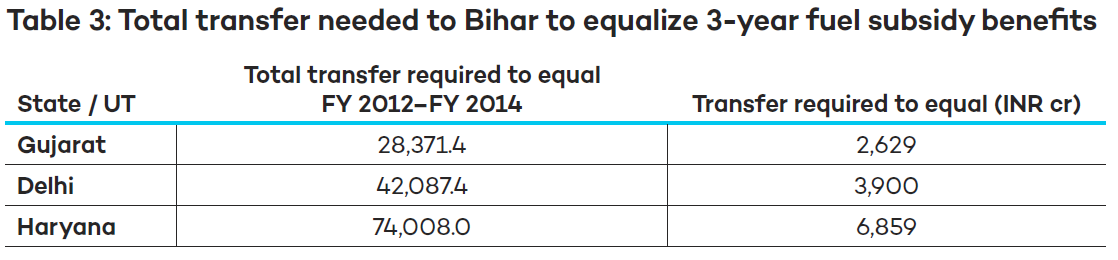

Table 3 calculates the total transfer required to equalize the transfer received in Bihar and that received in selected states for the three years to March 2014 (without accounting for inflation), and the per capita transfer that this would represent (using 2014/15 population estimates).

Were Bihar to receive a subsidy transfer equivalent to that received in Haryana for the three years to March 2014 alone, this would require an additional (compensatory) transfer of INR 74,008 crore (USD 11.4 billion) or INR 6,859 (USD 100) for every person in Bihar.[2] To achieve parity with Delhi would require a transfer of INR 42,087 crore (USD 6.5 billion), or INR 3,900 (USD 60) per person, and to achieve parity with Gujarat would require a transfer of INR 28,371 crore (USD 4.3 billion), or INR 2,629 (USD 40) per person.

You might also be interested in

What Drives Investment Policy-makers in Developing Countries to Use Tax Incentives?

The article explores the reasons behind the use of tax incentives in developing countries to attract investment, examining the pressures, challenges, and alternative strategies that exist.

What Is the NAP Assessment at COP 29, and Why Does It Matter?

At the 29th UN Climate Change Conference (COP 29) in Baku, countries will assess their progress in formulating and implementing their National Adaptation Plans. IISD’s adaptation experts Orville Grey and Jeffrey Qi explain what that means, and what’s at stake.

How to Track Adaptation Progress: Key questions for the UAE-Belém work programme at COP 29

UAE-Belem work program at COP 29: Emilie Beauchamp explains the complexity behind these talks and unpacks seven key questions that negotiating countries should address along the way.

COP 29 Must Deliver on Last Year’s Historic Energy Transition Pact

At COP 29 in Baku, countries must build on what was achieved at COP 28 and clarify what tripling renewables and transitioning away from fossil fuels means in practice.