The Art of Influence: How think tanks make a difference

"We like being thinkers, but we are thinkers with a purpose." Mark Halle explores how think tanks make a difference.

IISD and other policy research institutes often describe themselves as “think tanks” for short—a somewhat self-assured focus on the intellectual side of the policy development supply chain. Even if I tend to describe myself as the shallow end of the think tank, approaching retirement leads me to meditate on the proper role of institutions of our sort.

Merriam-Webster defines a think tank as “an organization that consists of a group of people who think of new ideas on a particular subject or who give advice about what should be done.” There are other definitions, but this one will do. The emphasis is on people and their intellectual power: a think tank consists of a group of people that thinks up new ideas, and the purpose of formulating those ideas is to offer them as a contribution to mapping possible pathways to change. In a nutshell, a think tank examines a field and seeks to formulate alternatives to current practice where this is less than optimal. A policy think tank does so by formulating alternative policy choices, solidly based on the analysis of evidence, that offer a chance of better outcomes if adopted.

Thinking is fun. Most people would welcome the opportunity to draw a pay-check for dreaming up new ways of doing things. But, to take a cue from patent law, the path from idea to intellectual product or property requires an innovative step and it must be susceptible to replication and scaling so as to secure a lasting improvement. It follows that policy advice must respond to the particular circumstances of time and place, and must reflect an understanding of how decisions are taken, and policies adopted, in the particular environment into which they are fed. And since that environment is in a state of constant flux, the policy options produced by think tanks must also evolve constantly. Think tanks that display flagging innovation are generally flagging in their influence and often in their financial health. A think tank must be at the cutting edge, or it is not much use. It can evolve into a consultancy or hew towards the academic end of the spectrum, relying on peer-reviewed papers and academic conferences to air the ideas, but neither is the proper berth for a think tank worthy of its name. Both modes can, and indeed at certain times should be part of the arsenal of a top level think tank, but that does not mean that it should be dominated by these activities.

So a think tank should be judged by a combination of innovation and relevance. Innovative thinking opens new perspectives, new ways to frame issues, and new interpretations of existing data. Everyone can think conventionally, and in any milieu there is almost always a strong inertia that keeps the conventional front and centre. There is no particular value in think tanks serving up standard fare, even if it plays into a familiar field and may improve the initial acceptability of the policy recommendations. Those that feed this sort of pap into decision-makers serve as a kind of capacity extension to government departments or parliamentary offices. That sort of service is readily available on the market. Being successful at that game requires technical skills and some experience, but it generally doesn’t require much—and certainly not innovative—thinking. Indeed, it may even shun invention.

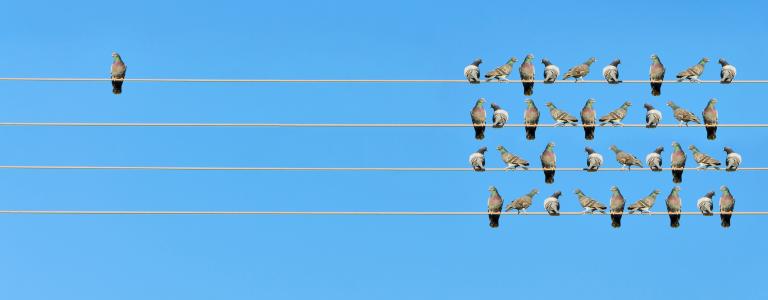

Instead, the notion of innovation—or innovative thinking—is central to the functioning of a think tank. Think tanks question mainstream thinking; they challenge orthodoxy; they propose new and different ways of thinking of things, of framing problems, of combining elements. They are open to promoting disruptive behaviour if it is the only way change can be achieved. If they do no challenge, they are not doing their job. If they do not make policy makers uncomfortable (at least at first), it is highly likely that the product of their thinking is not very innovative and that they have failed in their disruptive role.

At the same time, policy has to be formatted to run on the operating systems of the policy-makers in place. If not—if they are articulated in terms that derive from another culture or thought-system—they may be admired for their intellectual prowess but they will have little impact. Recommendations for reforming the financial system have to play to finance professionals or finance sector regulators. New suggestions for breaking the impasse in multilateral trade negotiations need to speak to the trade policy community, not the protesters at the barricades. Or at least they should target the politicians who decide on the scope and orientation of trade policy.

This is the art form—to strike the right balance between innovation (and its inherent challenge to orthodoxy) and relevance, judged by the tone and language with which it plays into the target community. But it is easy to neglect the art form and generate policy options that gather dust on the shelves. The temptation to be an accepted part of the target community can lead think tanks to cleave towards orthodoxy, to accept assumptions that instead must be challenged, and to smooth out the sharp edge of implied criticism. This is a mistake and one that should be avoided at all cost.

We like being thinkers, but we are thinkers with a purpose and that purpose is to show not only that there is a pathway to sustainable development but that no other outcome is acceptable. A think tank cannot afford simply to direct its products at a vague community of mildly-interested people. All of our products must have a target and reaching that target must result in positive change. They must remind the policy community to focus on the long-term goal of sustainable development that we supposedly all share but that in reality we regularly betray. If this means making our friends uncomfortable, we should remember that it is in the service of the right cause. It is what our mission dictates.

You might also be interested in

What Drives Investment Policy-makers in Developing Countries to Use Tax Incentives?

The article explores the reasons behind the use of tax incentives in developing countries to attract investment, examining the pressures, challenges, and alternative strategies that exist.

What Is the NAP Assessment at COP 29, and Why Does It Matter?

At the 29th UN Climate Change Conference (COP 29) in Baku, countries will assess their progress in formulating and implementing their National Adaptation Plans. IISD’s adaptation experts Orville Grey and Jeffrey Qi explain what that means, and what’s at stake.

How to Track Adaptation Progress: Key questions for the UAE-Belém work programme at COP 29

UAE-Belem work program at COP 29: Emilie Beauchamp explains the complexity behind these talks and unpacks seven key questions that negotiating countries should address along the way.

COP 29 Must Deliver on Last Year’s Historic Energy Transition Pact

At COP 29 in Baku, countries must build on what was achieved at COP 28 and clarify what tripling renewables and transitioning away from fossil fuels means in practice.