How Can We Work With Nature to Tackle Drought and Desertification?

Drought is one of the most devastating and pervasive challenges exacerbated by climate change. However, we can work to reduce its effects through nature-based solutions for land restoration and climate-smart agriculture.

Drought and Desertification

Drought has affected more people than any other natural disaster over the last 40 years, by drastically reducing both water quality and quantity, increasing the risk of disease and illness, and severely impacting livelihoods and nutrition through land degradation and food scarcity.

Extreme weather patterns, exacerbated by climate change, have resulted in some areas receiving a whole season’s rainfall in a single day, followed by an entire season with no rainfall at all. This variability is disastrous for communities, as it impacts soil health, agriculture, biodiversity, and hydropower, and often damages vital infrastructure. Such extremes leave land damaged through desertification: a form of land degradation in which drylands lose moisture and nutrients, becoming arid. This process can also be sparked through human activities, including agricultural factors like overgrazing and tilling, urban expansion and deforestation. Globally, more than 2 billion hectares of previously productive land has been degraded through desertification. That is an area twice the size of the United States!

Drought affects 1.84 billion people globally—that’s one in eight people

Currently, drought affects 1.84 billion people globally—that’s one in eight people. And it is set to get worse. The duration and frequency of droughts have increased by 29% since 2000, compared with the previous two decades. With further global warming, the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report found that every region is projected to experience more frequent heatwaves and droughts. By 2040, one in four children will be living in areas with extreme water shortages, with far-reaching impacts for future generations.

Drought is one of the most devastating and pervasive challenges exacerbated by climate change. However, we can work to reduce its effects by learning from nature.

As intense weather worsens, droughts increase in intensity and frequency and the Earth heats up, there will be devastating impacts on communities, people's livelihoods, food security, and global economies.

Drought: A global problem

Drought is a global concern. The greatest impact is on low- and middle-income countries, where 85% of people affected by drought reside, according to the World Bank. Agriculture is at the heart of these economies and is the sector most affected by drought, absorbing up to 80% of all direct impacts. Nearly 1.3 billion people rely on agriculture as their main source of income. As intense weather worsens, droughts increase in intensity and frequency and the Earth heats up, there will be devastating impacts on communities, people's livelihoods, food security, and global economies.

An average of 70 countries are affected by drought each year. The World Bank mapped recent drought and desertification hotspots from 2019 to 2022, demonstrating that this phenomenon is intensifying in five out of seven continents. These hotspots are illustrated in the below map, which will name the country when you hover over it.

Even the areas currently not affected by water scarcity will soon feel its effects due to climate-related migration. By 2030, an estimated 700 million people will be at risk of displacement from drought alone. More people will lose their livelihoods. They will be forced to flee their homes. Food will become harder to come by, as millions of hectares of land dries up and becomes uninhabitable. Drought has the potential to be a silent tsunami, sweeping across great swathes of our landscape over the next decade, with developing and least developed countries set to be the worst affected.

By 2030, an estimated 700 million people will be at risk of displacement by drought alone

Nature-based solutions—an antidote to drought

Nature is a resilient teacher. By employing nature’s own checks and balances for environmental extremes like drought and desertification, we can adapt the landscape to absorb some of the impacts of climate change.

Lessons found in nature are implemented through nature-based solutions (NbS) that help protect, restore, and sustainably use ecosystems while simultaneously providing human well-being, resilience, and biodiversity benefits. Examples of NbS include planting trees to improve air and soil quality, retain water, and provide wildlife habitats, or restoring wetlands to create buffer zones for flooding and to support erosion protection. This green approach to infrastructure services can complement—and sometimes replace—traditional grey infrastructure, such as concrete drains, seawalls, or breakwaters. Known as nature-based or natural infrastructure, this type of NbS can be employed to reduce the impacts of drought and desertification.

By 2040, one in four children will be living in areas with extreme water shortages, with far-reaching impacts for future generations.

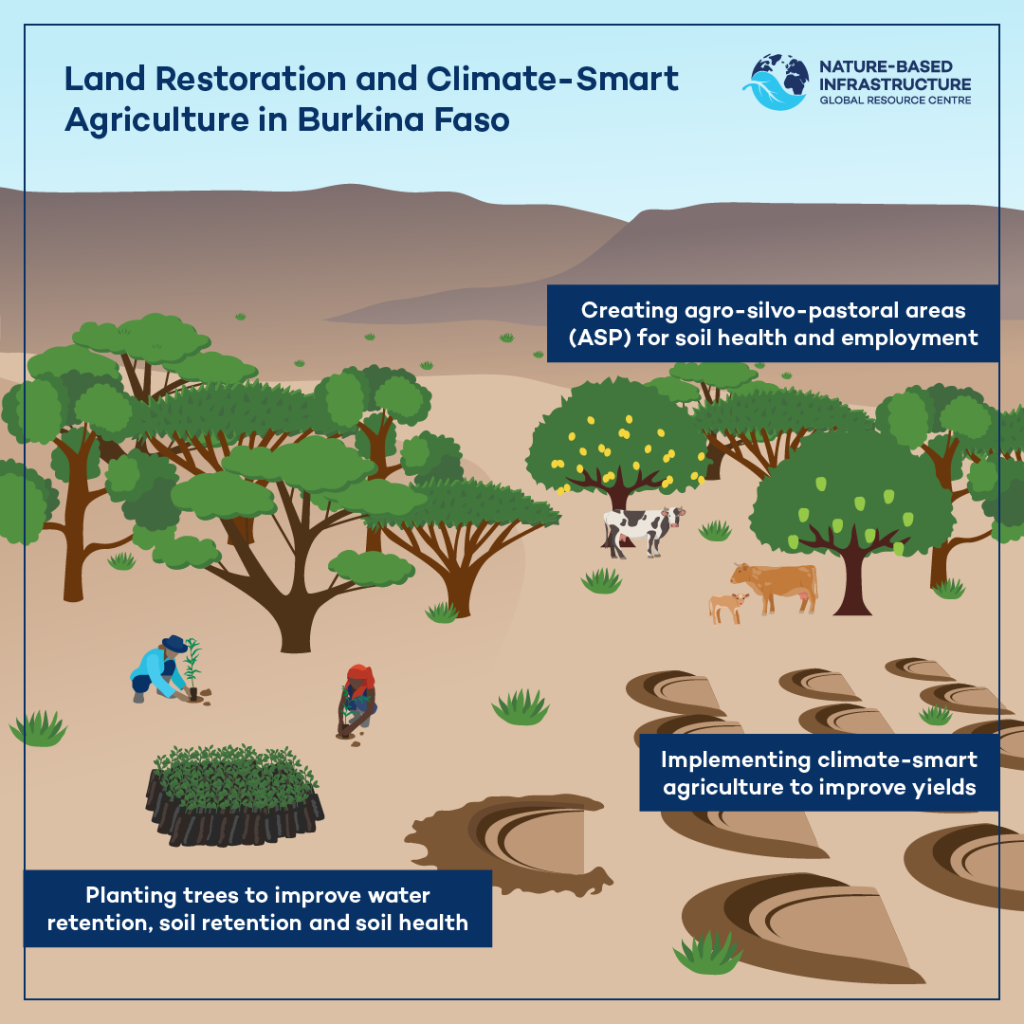

Combatting extreme droughts in Burkina Faso

In West Africa, Burkina Faso is experiencing severe impacts of climate change in the form of increasingly extreme rainfall and flooding events coupled with prolonged droughts. As a result, 46% of the country's arable land is now degraded. 80% of the population relies on agriculture for income, so drought and heat stress have detrimentally affected livelihoods and resulted in food scarcity.

To combat this, the government has proposed a new land restoration project that aims to regenerate over a third of the country’s total land cover. Through the Nature-Based Infrastructure (NBI) Global Resource Centre, an initiative aiming to demonstrate the investment case for nature-based approaches to climate change adaptation, IISD assessed three potential methods for land restoration: nature-based, hybrid and traditional grey infrastructure. Working with Burkina Faso’s Ministries of Finance and Agriculture, and supported by the NDC Partnership, the NBI Global Resource Centre developed financial and economic models, calculating that the nature-based approach performed better than traditional grey infrastructure, to the tune of USD 1.7 billion in added benefits to the community over 30 years.

Consisting of tree planting, climate-smart agriculture, regenerative agriculture practices, and the establishment of agro-silvo-pastoral areas (which integrate agriculture, grasslands, fruit crops, and livestock farming), the combined methods reduce land erosion, enhance water retention, and improve soil quality, thereby helping to restore the degraded land and boost agricultural productivity. This modelling demonstrates the remarkable potential of nature in restoring land and reversing desertification while creating a wealth of environmental, social, and economic benefits for rural communities.

At least 100 million hectares of healthy land, an area the size of Egypt, is lost every year.

Nature-based solutions are like a Swiss Army knife. They can help us tackle many problems in a single project: drought, flooding, climate-related migration, food scarcity, nutrition, public health, rural livelihoods and the economy, CO2 emissions, heat stress, biodiversity protection—and even social inequality. Because of its inherent resilience, working with nature—rather than against it—effectively reduces the impacts of drought and stops desertification in its tracks. But we need to deploy nature urgently; at least 100 million hectares of healthy land, an area the size of Egypt, is lost every year.

By 2030, an estimated 700 million people will be at risk of displacement from drought alone.

Three ways to include nature in climate adaptation

Increase awareness to demonstrate the diverse returns on investment

The first critical step for the successful implementation of NbS is to increase awareness of how nature can deliver these benefits by engaging with local communities, farmers, policymakers, and investors.

IISD has worked on a variety of projects doing just that all over the world. The Nature for Climate Adaptation Initiative developed an online course to raise awareness of the benefits of ecosystem-based adaptation and equip learners with transferable and replicable skills in designing and implementing these initiatives. Furthermore, in Manitoba, Canada, our Natural Infrastructure for Water Solutions team worked with the Seine Rat Roseau Watershed District to demonstrate the financial and economic benefits of their Water Retention program to local farmers and communities. The program helps protect farms from floods and drought, conserves habitats, and improves water quality downstream. David Wiens, a dairy producer in the district, said of the program: “My initial concern was about having the pastures flooded for a period of time. But when I understood the design, it became clear that it would actually be win–win.”

We can also tackle social inequalities by empowering underrepresented groups to pave the way for nature-based approaches. For example, a project that aimed to improve women’s land ownership in Rwanda also increased investments in soil conservation. In the Amazon, securing land rights for Indigenous People helped reduce deforestation. The impacts of the climate and biodiversity crises interact with social and gender inequalities, disproportionately affecting marginalized populations, and NbS initiatives must take this into account to boost societal benefits.

Collaboration is key—consider drought as part of a wider problem

Drought and degraded land are not isolated issues. They have far-reaching impacts and implications for all areas of society, including public health, agriculture, the economy, and migration. An intersectional, unified approach between local communities, farmers, and policy-makers is crucial to gaining investment. Government ministries must come together to find solutions for climate change adaptation and mitigation. Local governments need to work with farmers and communities to support projects on the ground. Non-governmental organizations and governments can align with private investors to encourage financial flows to land restoration projects that sequester carbon and improve agricultural yields. Overall, stakeholders must break out of their silos and work together with an intersectional and coordinated approach to the problem.

Encourage and implement climate-smart and regenerative agricultural practices

In areas worst affected by drought, raising awareness, and funds and providing training for agricultural communities on implementing climate-smart and regenerative agricultural practices is crucial to maintaining land-restoration progress. Depending on the location, these practices can include reduced- and no-tilling techniques, “half-moons” or “earth smiles” (a traditional method of rainwater collection and soil restoration in the Sahel), keeping soil covered to prevent erosion, increasing crop diversity to boost soil health, nature-based water retention methods like channel rehabilitation, planting agroforests, creating agro-silvo-pastoral areas, and many more. These strategies are necessary to both recover already degraded land and prevent further desertification as droughts worsen with climate change.

Drought has been a concern for agriculture around the globe. Even in areas that are not directly affected to the extreme levels seen in low- or middle-income countries, action needs to be taken. By implementing NbS and making changes now to agricultural practices, farmers, communities, and policymakers can do their part to lessen future impacts of the climate crisis.

Learning more about how nature can help

With drought intensifying in five of seven continents, as well as the other climate crisis effects we are facing globally, it can feel a bit hopeless. However, if we collaborate on solutions, using nature as our example, we can improve our climate adaptation strategies locally and globally.

Here at IISD, we have a number of ways for you to explore solutions, learn from case studies, and discover more about working with nature for climate adaptation.

- Nature-Based Infrastructure (NBI) Global Resource Centre

- Natural Infrastructure for Water Solutions (NIWS)

- SUNCASA - Resilient Cities. Natural Solutions.

- Climate Adaptation and Protected Areas (CAPA)

- Nature for Climate Adaptation Initiative (NCAI)

- Natur’ELLES

- FERMA

- Nature-based Solutions to Enhance Resilience to Climate Change (NATALIE)

You might also be interested in

IISD Annual Report 2022–2023

At IISD, we’ve been working for more than three decades to create a world where people and the planet thrive. As the climate crisis unfolds on our doorsteps and irreversible tipping points loom, our team has been focused more than ever on impact.

IISD Annual Report 2023–2024

While IISD's reputation as a convenor, a trusted thought leader, and a go-to source on key issues within the sustainable development field is stronger than ever, the work happening outside the spotlight is just as valuable.

For Nature-Based Solutions to Be Effective, We Need to Work with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities

Nature-based solutions have been praised as a promising approach to tackling the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. But some Indigenous Peoples and local communities are questioning the legitimacy of the concept and what it symbolizes. It is time to listen to what they have to say.

The 'spongy' cities of the future

Tangled mats of muddy vegetation line the footpaths of Underwood Park, a narrow stripe of green winding along a creek beneath the small volcanic cone of Ōwairaka (Mt Albert) in Auckland, New Zealand. In the water, clumps of sticks and the occasional plastic bag are marooned on protruding rocks and branches.